Why can’t Gangsters Buy Real Works of Art?

By Abel Cervantes

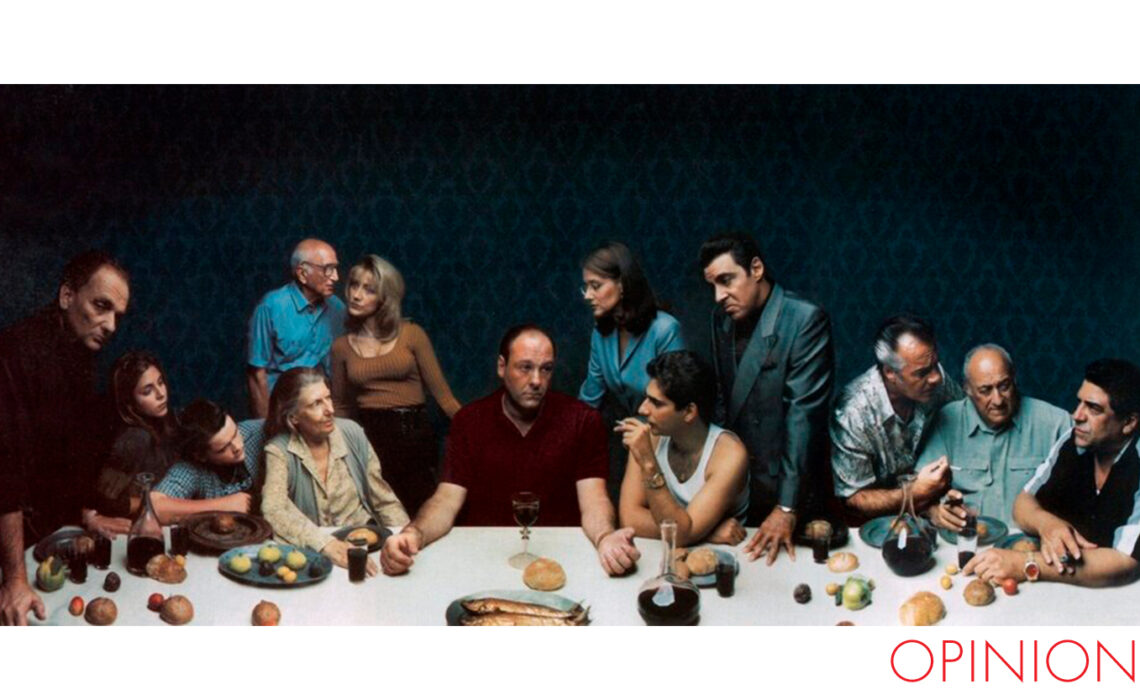

We are in 1999. HBO prepares its most recent television series without knowing that it will change history forever.

Along with The Wire (also produced by HBO), The Sopranos offered an audiovisual format recently seen in which the chapters had a continuity, as if it were a full-length film. They called it Megafilme. For the first time television allowed the characters to have a development of 70 or 80 hours to observe their chiaroscuro. Since then, various production companies have understood that current viewers demand different ways of approaching audiovisual language. The issue comes to mind because The Sopranos are on everyone’s lips again. Soon the film of The Sopranos will be released starring Michael Gandolfini, son of the unforgettable James Gandolfini, who portrayed Tony Soprano superbly.

Beyond the audiovisual merits of Los Sopranos, and its undoubted importance for understanding North American culture at the beginning of the 21st century, I would like to dwell on one of the phenomena that I have observed with more interest in recent times: the appearance of contemporary art in the least expected formats.

As some contemporary critics and thinkers have already documented, contemporary art is increasingly related to everyday life. It is not surprising that an artist is responsible for the design of the inauguration of a massive event (as happened with Cai Guo-Qiang at the Beijing Olympics) or that contemporary artists are discussed in popular series (examples are from The Simpsons a Lilyhammer).

In one of the first chapters of the first season, Tony Soprano’s son meets a girl with whom he falls in love. The Soprano family (a kind of nouveau riche) has Lladró pieces inside their home. Tony’s son’s friend, on the other hand, has authentic pieces of Picasso art. Historically, the acquisition of art is associated with education and culture. A family like The Sopranos, whose money comes from illegal sources, should not have enough education to pay a large amount of money for a piece of art: although art can be used as an investment resource, after all it is a Lifestyle. Why can’t gangsters have fancy art pieces?

It is known that in countries like Mexico (which, according to journalist and writer Roberto Saviano, is the capital of cocaine) the big gangsters spend on works of art. Why do they have to? What is the engine that drives you to acquire a piece that could belong to a museum or gallery? Just as famous businessmen need to validate their socioeconomic status before the world by building museums or showing off their art pieces, organized crime needs to acquire expensive (not sophisticated) works of art to validate before society.

A work of art cannot buy months without interest. Although it serves as an object that can raise its price over time, in the end it is intended to bring pleasure to whoever paid for it. A piece of art is a way of saying: yes, I bought this object just to look at it. Why then is a mobster unable to have an enviable collection for art critics? What are the mechanisms of art that prevent a person who ascends the economic pyramid from not having sufficient criteria to buy a work by Louise Bourgeois? If contemporary art is part of everyday life, how is it related to those minority groups that move in illegality?