Ada Trillo

ARTIST

Ada Trillo (Born and raised in the U.S-Mexican border region of Juárez and El Paso.)

PHOTOGRAPHY

Artistic influences: Mary Ellen Mark, Sebastián Salgado, Diane Arbus, Isabel Iturbide.

DECEMBER 2021

BEYOND THE BORDERS, A CONVERSATION

WITH Ada Trillo

BY REGINA DE CON COSSÍO

Photographs Courtesy of the artist

Ada Trillo’s work in photography is mainly focused on topics like race, violence, social classes and migration. Justice is very close to the heart of her images. Her vision is deeply defined by what every human relationship should have: dignity. Through empathy she approaches her protagonists . Along her photographies we are confronted with scenes where humanity -in the context of injustices or violence- stounds out in extreme beauty despite the horrors of reality.

Regina De Con Cossío: You have long questioned the phrase “a picture is worth a thousand words”. Perhaps as in no other artistic disciplines, images are related to words in order to create meanings. I’m not saying that they depend on them, but they have made a link that affects the viewer. On some occasion you mentioned that you have dyslexia and that it is a problem for you to resolve this connection. How does this relationship between images and words influence your photographic production process?

Ada Trillo: So for me dyslexia is not a problem necessarily, is an asset, I have learned that disabilities, because I have actually three disabilities, are something that you can catastrophize on, feel sorry for yourself or you can do something different. I have a different eye, so my eye is a little bit different from a person that perhaps has a completely linear way of mind, right? So that’s why my compositions are a little bit more different. What I do for the dyslexia, it has been—again—an asset and it makes me closer to the people because what I do is write in my journals their story, or I do it with my iPhone, recording and from there it gets transcribe into English or whatever language of the exhibit word I am going to be showing right? So it is the person’s own words, not mine, and then making that person words sounds pretty.

RDCC: It’s more affective, right?

AT: Yeah it’s their words, it’s them. It’s a first person, instead of me putting them as the word that I hate “subject”. For me they are the ” protagonists”.

RDCC: When you photograph a socially difficult moment (The Beast, Black Live Matters, etc.) ethical and moral situations are triggered in many directions. I imagine, for example, questions like: should I portray this or that? Why show this image and not the other? What other questions go to your head when you go to photograph events like these?

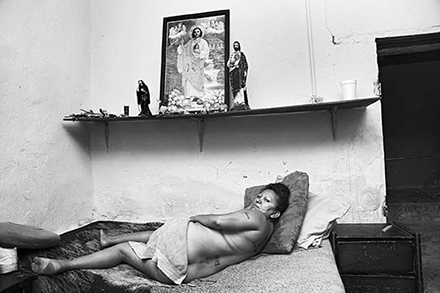

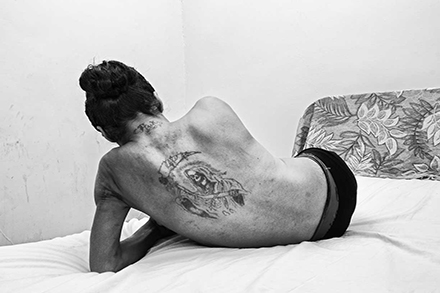

AT: The first is dignity. Am I giving dignity to this person? The other one is, just to give you an example from one project, with the Sexual Workers Project in Juárez. It was very important to me that I had a close relationship with them, that I was just not this outsider, that I was there listening because sometimes people just want to be listened to, they don’t want advices, they don’t want you to put you to sense or whatever they just want to be listened an put attention to clearly, do you know? And being able to put all that pain out in a safe space, and I linking that safe space, and then they trust me with me taking the picture and they know, based on our conversation, there’s mutual trust, that I’m not going to trick them or do something bad with those images, and that’s why I’m also very protective of the How did I get there project and it’s under code only for people in the educational purposes in my website because I don’t want anything, a third person coming into manipulating the image of a person that I care for a lot.

RDCC: How do you feel to capture a painful maybe inconvenient or even dangerous “moment” or scene?

AT: It’s capturing essence and documenting history, right? History must be documented, otherwise the same atrocities keep happening again and again and again. For instance, in the case of How did I get here project, what do I do with these pictures? What is the responsibility with them? What was the responsibility, I don’t know if you know this already is we built a safe house in Juárez with all the proceeds of those pictures, so hundred percent of the pictures of the money of these pictures went, for the first exhibit, to build these shelter in Juárez for the women to be reunited with their kids that “El DIF” have taken away, and it was through the Oblate Nuns, (Las Madres Oblatas del Sagrado Redentor), it was with them that we build the safe house.

And what do you or what do I also do for the community then? For example with “Coco” we’re still friends and I got her out of that situation for life because her picture is in the Museum of Art, in Philadelphia. I felt that, as a thank you to her, I would make responsable for her and her leaving that awful place. In Juárez is horrible, she was in the street, in the floor, in the worst conditions you can imagine, and I have to get her outta there, and that’s my duty to her forever, until I died.

RDCC: How do you deal with the fact that some of your images portraying complicated events will become cultural products that can eventually be considered art, can be displayed in a gallery or can be sold?

AT: That is a great question because I don’t know if you’re aware of this but in the documentary world there’s a lot of rules and one of those rules is that you cannot feed the people that you photographe and I have a huge problem with that rule, so that is why I consider myself an artist, because if I took a picture of a boy lets say in the shelter 2 days ago because I travel with them, I don’t just stay in a hotel, I travel with them, I stay with time, I eat with them, everything with them, so if I took a picture—let’s say two days ago—and this boy run out of money and now he’s crying because he’s so hungry and he’s an unaccompanied minor traveling by himself so since I are took a picture, if I am a documentarist or a journalist I can’t help him under certain rules but if I am an artist I can do whatever the hell I want. Also for a journalist they’ve been to school, they gone to school, they pay their dues, they work for newspapers, they have a long training. My training is or my background is in art and things should be remember like, I mean Graciela Iturbide for instance, Manuela Álvarez Bravo for instance, documenting horrible situations and still they are considered art it depends on the practice and do you how you feel yourself.

RDCC: Many of your photos capture socially difficult moments in many respects they go be confused with images of photojournalism but they are not, so what difference do you find between your photos and those of photojournalism?

AT: Photojournalism is in color and it seems very rare that they let black and white, when I show in a magazine or in a publication like The Guardian or some other journals, it’s stablish that my work will be shown as black and white and it’s like a certain, because I don’t work for the magazine or the newspaper, you know? I am independent so the black and white you use it more like an artistic, I don’t know in historical view to the work versus color, which is my next project, it is in color, or I am trying to make it in color but I’m having an extremely difficult time. I think that’s how you measure, also if you use the lofter or the Da Vinci rule. What rules are you using to create the work, where are you putting the subject, in the side, in the middle or what composition are you making because you can easily be portraying drama? I can be portraying a very horrible situation like “The beast” for instance when the train is actually moving but it’s my choice, and my eye, and my training, which is okay, what’s the position of this image, where can I find it, what do I want to say with this image, and what I told you before does it work like a painting? Does it work back and a bit around?

RDCC: In social sciences it is said that when a researcher approaches the subject of study he alteres it. Do you agree with this sentence or how do you think the presence of a photographer like you influences the events you capture?

AT: No, because I travel. As I told you, as one of them I become part of the community and I travel alone so it’s like a group of 7000 people in a caravan are not going to change over me. They are not because they are the majority so if I become the minority I have to apply the rules that they establish and follow them. Even in this community, it is a community where they are the majority and I am the minority, how do I integrate myself? As much as possible. I mean I’m never going to be one of them and how do I integrate myself as much as possible and we can connect to good human beings, because that is what we are, she’s a very good human being and I am a good human, being we are interacting and we are building this beautiful friendship does it matter what she does and doesn’t matter what I do.

RDCC: Your work largely revolves around the concept of border. Geographic, political, social boundaries. But your images are also on a border: that of photography and photojournalism. The one with the image and the word. What do borders mean to you?

AT: For me yes, those are “borders” but it is also not the word just in a geographical way. If you translate from the Spanish “Frontera” more in the sense of edges, or barriers, you can see how the concept also points out a sense of classism. A huge problem that exists so largely in Central America, Mexico and overall Latin America. That is comparable also with racism in the United States. For example, when you see people with darker skin, the opportunities that are given to them by government and all that are different. The truth is I see borders more as a matter of social justice. As we are almost in 2022, is this like the legacy that I want to leave?

For example, this girl Silvia, just to give you an example: she fell, hit her spine and they did not give her medical attention in the hospital in the insurance of Juárez because she was a sex worker. If they had given her treatment, she would not have had to be on crutches for the rest of her life. However, she got infected and they did a horrible thing, it is that classism is that judgment when it was the job of the receptionist’s nurse to give her a number and let her enter to the doctor, but only because of her physical appearance she was denied that she had a very serious spine problem with crutches forever.

MAS ALLÁ DE LAS FRONTERAS

UNA CONVERSACIÓN CON ADA TRILLO

POR REGINA DE CON COSSÍO

Fotografías cortesía de la artista

El trabajo de Ada Trillo en fotografía se centra principalmente en temas como la raza, la violencia, las clases sociales y la migración. La justicia está muy cerca del corazón de sus imágenes. Su visión está profundamente definida por lo que toda relación humana debe tener: dignidad. A través de la empatía se acerca a sus protagonistas. A lo largo de sus fotografías nos enfrentamos a escenas donde la humanidad -en el contexto de injusticias o violencia- se destaca en extrema belleza a pesar de los horrores de la realidad.

Regina De Con Cossío: Durante mucho tiempo has cuestionado la frase “una imagen vale más que mil palabras”. Quizás como en ninguna otra disciplina artística, las imágenes se relacionan con las palabras para crear significados. No digo que dependan de ellos, pero han hecho un vínculo que afecta al espectador. En alguna ocasión mencionaste que tienes dislexia y que es un problema para ti resolver esta conexión. ¿Cómo influye esta relación entre imágenes y palabras en tu proceso de producción fotográfica?

Ada Trillo: Para mí, la dislexia no es necesariamente un problema, es una ventaja. He aprendido que las discapacidades, porque en realidad tengo tres discapacidades, son algo que puedes catastrofizar, o sentir lástima por ti mismo o puedes hacer algo diferente. Tengo un ojo diferente, así que mi visión es un poco diferente al de una persona que quizás tenga una mentalidad completamente lineal. Por eso mis composiciones son un poco más diferentes. La dislexia ha sido —nuevamente— un activo y me acerca a la gente porque lo que hago es escribir en mis diarios su historia, o lo hago con mi iPhone, grabando y de ahí se transcribe al inglés o al idioma de la palabra de exhibición que voy a mostrar. Entonces, hablo desde las propias palabras de la persona, no las mías, y luego hago que las palabras de esa persona suenen bien.

RDCC: Es más afectivo, ¿no?

AT: Sí, son sus palabras, son ellos. Es en primera persona, en lugar de ponerlos como la palabra que odio “sujeto”, para mí son los “protagonistas”.

RDCC: Cuando fotografías un momento socialmente difícil (La Bestia, Black Live Matters, etc.) se desencadenan situaciones éticas y morales en muchas direcciones. Me imagino, por ejemplo, preguntas como: ¿debo retratar esto o aquello? ¿Por qué mostrar esta imagen y no la otra? ¿Qué otras preguntas se te vienen a la cabeza cuando vas a fotografiar eventos como estos?

AT: La primera es la dignidad. ¿Le estoy dando dignidad a esta persona? Por otra parte, solo para darle un ejemplo de un proyecto, con el Proyecto de Trabajadoras Sexuales en Juárez. Era muy importante para mí tener una relación cercana con ellas, que se dieran cuenta que no era una extraña, que estaba allí escuchando porque a veces la gente solo quiere ser escuchada, no quiere consejos, solo quieren que los escuchen y les presten atención claramente, ¿sabes? Y poder sacar todo ese dolor en un espacio seguro y tras este proceso me confían que tome la foto y saben, según nuestra conversación, hay confianza mutua, que no estoy ahí para engañarlas o hacer algo malo con esas imágenes, y es por eso que también soy muy protectora con el proyecto, en la página web cuenta con un código y se presta solo para fines educativos, porque no quiero que nada malo pase, que una tercera persona entre y manipule la imagen de una persona que me importa mucho.

RDCC: ¿Cómo te sientes al capturar un “momento” o escena dolorosa, tal vez inconveniente o incluso peligrosa?

AT: Busco capturar la esencia y documentar la historia. La historia debe documentarse, de lo contrario, las mismas atrocidades siguen ocurriendo una y otra vez. Por ejemplo, en el caso del proyecto Cómo llegué aquí, ¿qué hago con estas imágenes? ¿Cuál es la responsabilidad con ellos? Cuál fue la responsabilidad, no sé si ya lo saben, pero construimos una casa de seguridad en Juárez con todo lo recaudado de esas fotos, entonces el cien por ciento del dinero de estas fotos se fue a construir estos albergues en Juárez para que las mujeres se reúnan con sus hijos que “El DIF” les ha quitado, y fue a través de las Monjas Oblatas, (Las Madres Oblatas del Sagrado Redentor), fue con ellas que construimos la casa de seguridad.

¿Y qué haces tú o qué hago yo también por la comunidad entonces? Por ejemplo con “Coco” seguimos siendo amigas y la saqué de esa situación de por vida porque su cuadro está en el Museo de Arte, en Filadelfia. Sentí que, como agradecimiento hacia ella, me haría responsable de que ella dejara ese horrible lugar. En Juárez es horrible, ella estaba en la calle, en el piso, en las peores condiciones que te puedas imaginar, y tuve que sacarla de ahí, y ese es mi deber para con ella por siempre, hasta que me muera.

RDCC: ¿Cómo lidias con el hecho de que algunas de sus imágenes que retratan eventos complicados se convertirán en productos culturales que eventualmente pueden considerarse arte, pueden exhibirse en una galería o pueden venderse?

AT: Esa es una gran pregunta porque no sé si eres consciente de esto, pero en el mundo del documental hay muchas reglas y una de esas reglas es que no puedes alimentar a las personas que fotografías y tengo una gran problema con esa regla, entonces por eso me considero una artista, porque si le saqué una foto a un niño digamos en el refugio hace 2 días, porque yo viajo con ellos, no me quedo en hoteles, viajo con ellos, me quedo con ellos todo el tiempo, como con ellos, todo con ellos, entonces si yo tomé una foto, digamos hace dos días, y este niño se quedó sin dinero y ahora está llorando porque tiene mucha hambre y es un menor no acompañado, viaja solo, así que como yo tomé una foto, si soy documentalista o periodista no puedo ayudarlo bajo ciertas reglas, pero si soy artista puedo hacer lo que me dé la gana. También los periodistas han ido a la escuela, han ido a la escuela, pagan sus cuotas, trabajan para los periódicos, tienen una larga formación. Mi formación es en el arte y las piezas deben pensarse como arte, me refiero a Graciela Iturbide por ejemplo, Álvarez Bravo por ejemplo, documentando situaciones horribles y aún así se consideran arte, depende de la práctica y cómo te sientes tú mismo.

RDCC: Muchas de tus fotos capturan momentos socialmente difíciles en muchos aspectos se pueden confundir con imágenes de fotoperiodismo pero no lo son, entonces ¿qué diferencia encuentras entre tus fotos y las de fotoperiodismo?

AT: El fotoperiodismo es en color y es muy raro que trabajen el blanco y negro, cuando muestro en una revista o en una publicación como The Guardian o alguna otra revista, se establece que mi trabajo se mostrará en blanco y negro, porque yo no trabajo para la revista o el periódico, ¿sabes? soy independiente, así que el blanco y negro lo usas en una forma más artística, mi próximo proyecto es en color o estoy tratando de hacerlo en color, pero estoy pasando por un momento muy dificil. Creo que así es como mides, también si usas el lofter o la regla de Da Vinci. ¿Qué reglas estás usando para crear el trabajo, dónde estás poniendo el tema, en el lado, en el medio o qué composición estás haciendo porque puedes estar retratando fácilmente el drama? Puedo estar representando una situación muy horrible como “La bestia”, por ejemplo, cuando el tren se está moviendo, pero es mi elección, mi ojo y mi entrenamiento, lo cual está bien. ¿Cuál es la posición de esta imagen? ¿Dónde puedo encontrarla?, ¿qué quiero decir con esta imagen, y lo que les dije antes funciona como un cuadro? ¿Funciona hacia atrás y un poco alrededor?

RDCC: En ciencias sociales se dice que cuando un investigador se acerca al tema de estudio lo altera. ¿Estás de acuerdo con esta frase o cómo crees que influye la presencia de un fotógrafo como tú en los hechos que captas?

AT: No, porque viajo con ellos, como te dije, como uno de ellos, me hago parte de la comunidad y viajo, así que es como un grupo de 7000 personas en una caravana no va a cambiar por mi presencia. No van a cambiar porque son la mayoría entonces si me convierto en minoría tengo que aplicar las reglas que ellos establecen y seguirlas. Incluso en esta comunidad, es una comunidad donde ellos son la mayoría y yo soy la minoría, ¿cómo me integro? Cuanto más se pueda. Quiero decir, nunca voy a ser uno de ellos por lo cuál me integro lo más posible, y podemos conectarnos como buenos seres humanos, porque eso es lo que somos, ella es un muy buen ser humano y yo soy un buen humano, ya que estamos interactuando y estamos construyendo esta hermosa amistad, importa lo que haga ella y no importa lo que haga yo.

RDCC: Tu trabajo gira en gran medida en torno al concepto de frontera. Límites geográficos, políticos, sociales. Pero tus imágenes también están en una frontera: la de la fotografía y la del fotoperiodismo. El de la imagen y la palabra. ¿Qué significan las fronteras para ti?

AT: Para mí sí, esas son “fronteras”, pero tampoco es la palabra solo de manera geográfica. Si traduces del español “Frontera” más en el sentido de bordes o barreras, puedes ver cómo el concepto también señala un sentido de clasismo. Un gran problema que existe en gran medida en América Central, México y en general América Latina. Eso es comparable también con el racismo en los Estados Unidos. Por ejemplo, cuando ves personas con piel más oscura, las oportunidades que les da el gobierno y todo eso son diferentes. La verdad es que veo las fronteras más como una cuestión de justicia social. Como estamos casi en 2022, ¿es este el legado que quiero dejar?

Por ejemplo, esta niña Silvia, para ponerte un ejemplo: se cayó, se golpeó la columna y no le dieron atención médica en el hospital del seguro de Juárez porque era trabajadora sexual. Si le hubieran dado tratamiento, no habría tenido que andar con muletas por el resto de su vida. Sin embargo, ella se contagió y le hicieron una cosa horrible, es que el clasismo es ese juicio, cuando era trabajo de la enfermera, de la recepcionista darle un número y dejarla entrar al médico, pero solo por su apariencia física se le negó que tuviera un acceso al médico y esto resultó en un problema de columna muy grave, dejándola en muletas para siempre.