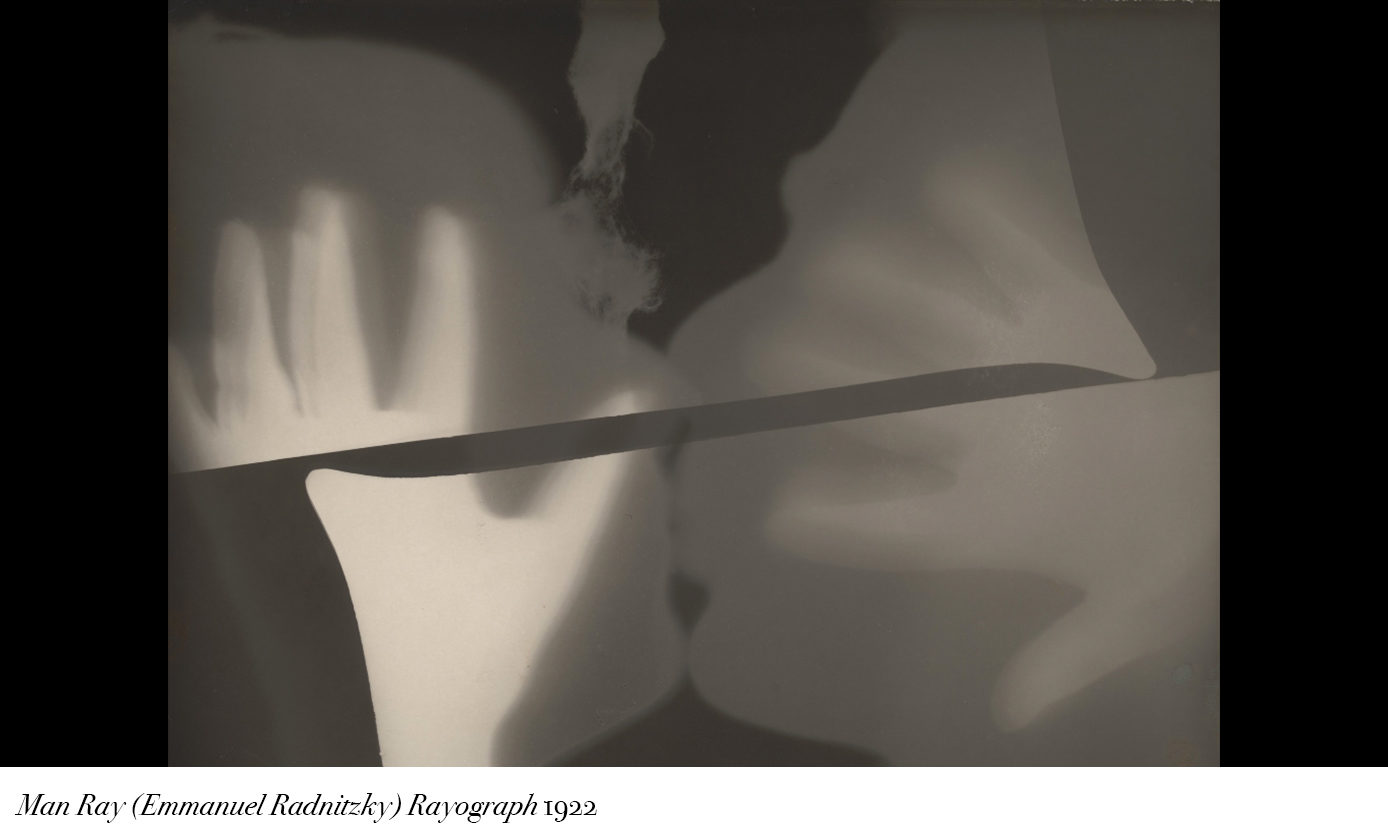

Can a scientific image be a work of art?

By Sybaris Collection

The Museum of Modern Art in New York (MoMA) has incorporated into its collection the first photograph of a black hole, which is 55 million light years from our planet. The image is the result of about two years of research in which a series of telescopes located in different parts of the world were aligned to become a kind of Earth-sized telescope. With this event, MoMA opens new routes on one of the most interesting questions of recent times, which cannot be answered from a single perspective: what is art?

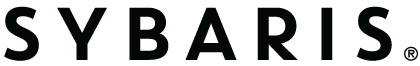

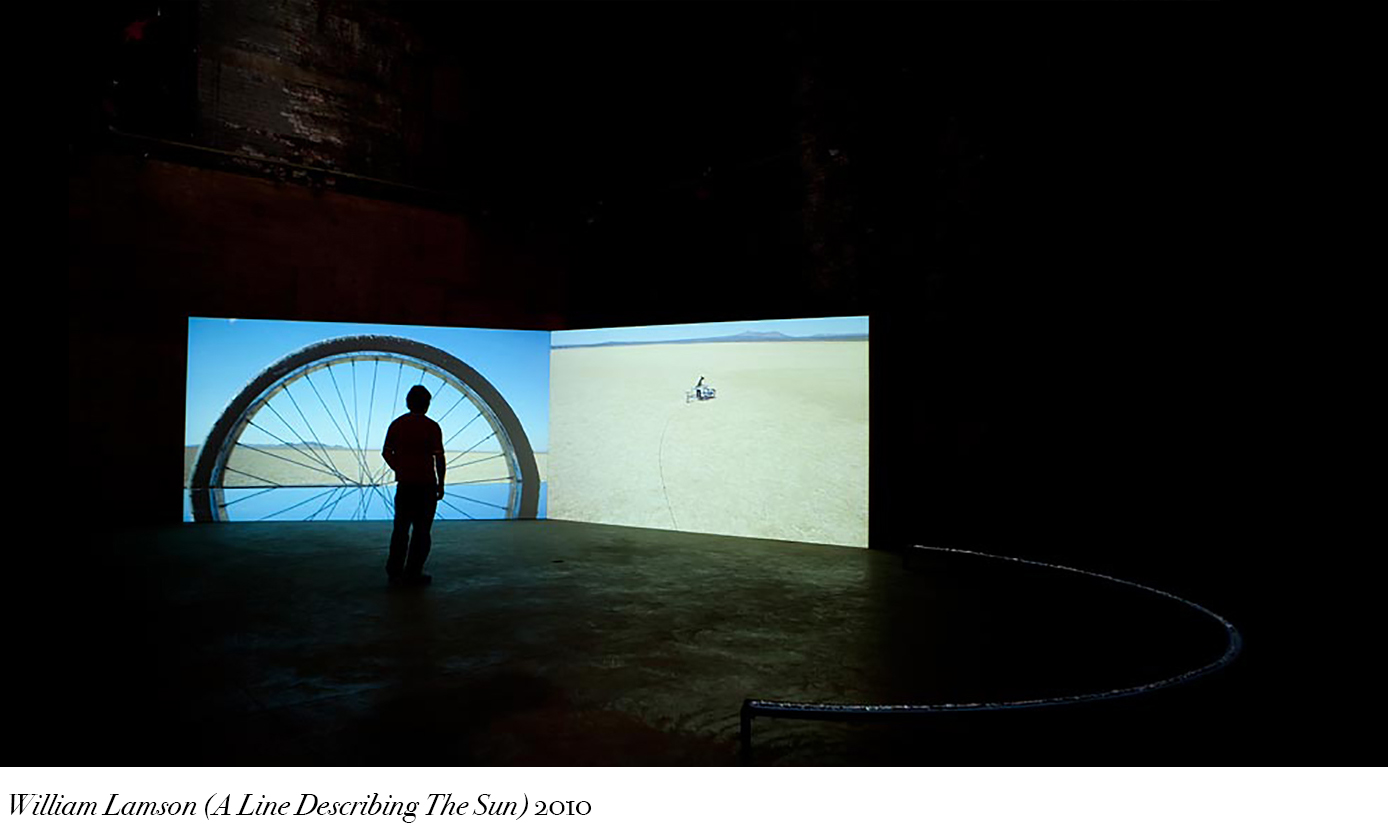

The link between science and art has resulted in a series of stimulating experiments, to say the least. There are few artists behind an image or an installation that have interests related to matter, time, light or speed. One of the most striking phenomena is that where science, politics, economy and society merge to describe the geological alteration that Earth has suffered due to human presence. William Lamson (A Line Describing The Sun, 2013), Tomás Saraceno (Aero Solar Museum, 2007), Adrián Villar Rojas (Today We Reboot The Planet, 2013), Shezad Dawood (Towards The Possible Film, 2014) and Olafur Eliasson (Ice Watch, 2015) are some of the most recognized names that have investigated this link between art and science that has been termed as the Anthropocene era.

With the acquisition of a photograph of a black hole, MoMA begins two paths: the first one very similar to that of the first photograph of the Earth taken by Apollo 8 at the end of the 60’s: after being released, the then president Johnson gave an image to different leaders from different countries. Similarly, the science museums of the United States exhibited it not only as a vestige of nature but as a work of art. The second, perhaps more complex and difficult to decipher, open up new questions for museums, galleries, artists and collectors. What does it take for a phenomenon of nature – be it outer space or Earth – to have the attributes to be displayed inside a museum or be part of the collection of a gallery or a particular collector?