Nicole Chaput

ARTIST

NICOLE CHAPUT (MÉXICO, b. 1995)

Escultura, Instalación

ABRIL, 2022

Pinturas hinchadas: el cuerpo de la mujer desde la metáfora y la autoficción

POR REGINA DE CON COSSÍO

Imágenes cortesía de la artista

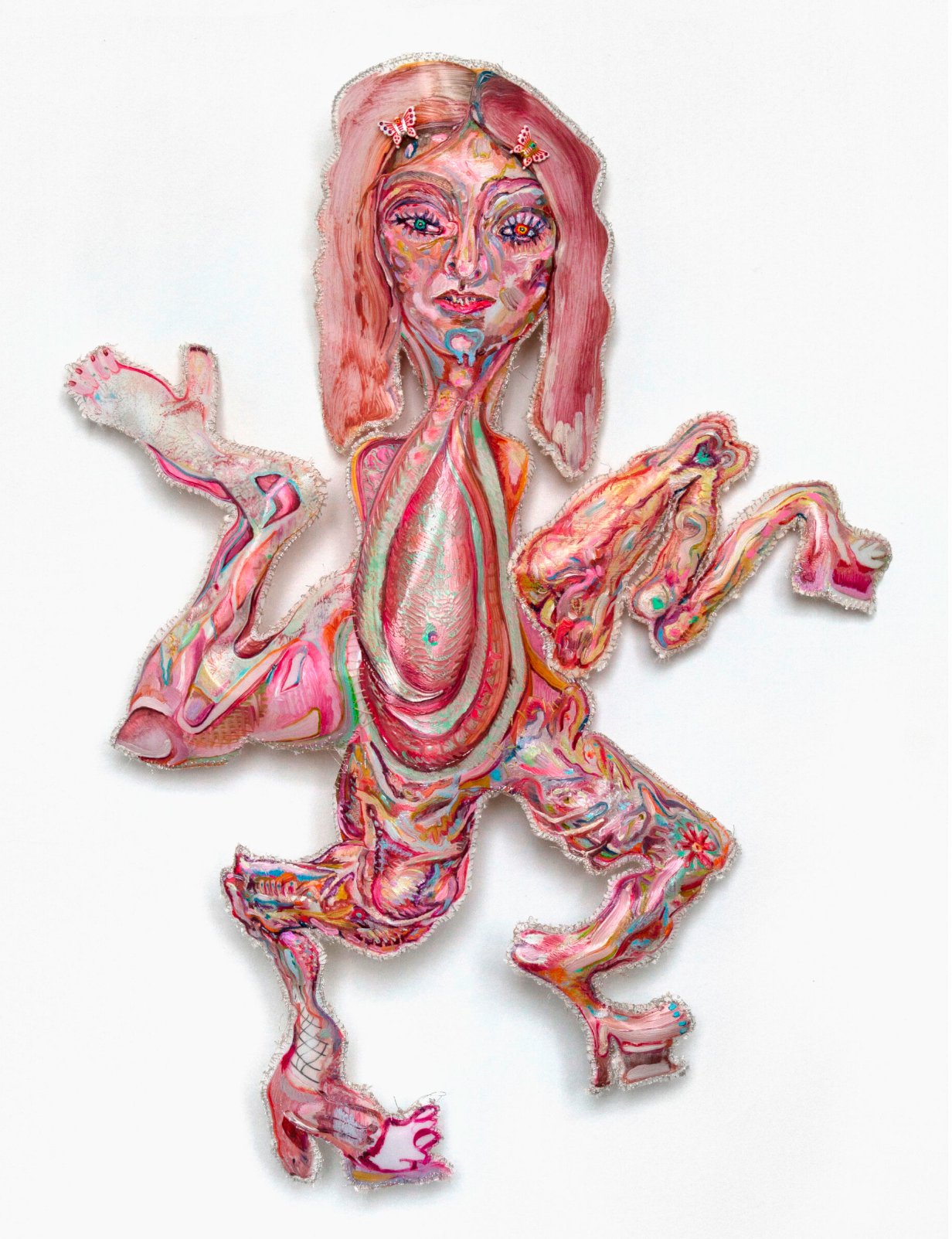

Retrato de la artista con mano hecha de fibras y textiles varios.

Foto: colaboración entre Renata Cruz Lara Guerra y Nicole Chaput.

El trabajo de Nicole Chaput parte de un proceso de introspección que, al mismo tiene, deviene en una crítica a los imaginarios culturales en torno al cuerpo de la mujer. En sus pinturas hinchadas, como ella misma las llama, converge una serie de cargas simbólicas impuestas a la anatomía femenina desde el arte, el cine, la ciencia, la moda, el pop, etc., que luego son transformadas en objetos pictórico-escultóricos de ficción. En esta conversación, Chaput profundiza sobre las bases de su trabajo.

Regina de Con Cossío: Tus piezas a menudo parecen referencias al mundo de la medicina: los órganos están expuestos, la disección de los cuerpos simulan un estudio analítico. ¿Cómo relacionas tu proceso artístico con la medicina, en particular con la anatomía?

Nicole Chaput: La agresión de los corales ocurre cuando estas criaturas escupen sus tripas para atacar a sus vecinos y defender su territorio. La boca vomita materia visceral, empujando las enzimas digestivas para disolver a sus adversarios. Después de asfixiar a las criaturas adyacentes, el coral se traga sus vísceras. Al igual que el coral, el derrame interno se convierte en una estrategia de resistencia y supervivencia en mi práctica artística donde reivindico el territorio y la agencia de mi cuerpo; sus límites en peligro regular de ser traspasados y extinguido

El interior de los cuerpos femeninos en la medicina occidental ha sido interpretado y analizado para ser oprimido y marginado, de modo que tanto el interior (capacidades reproductivas) y el exterior (objetificación, sexualizacion, educaciones de deseo) han sido articulado según miradas y agendas patriarcales. Desde las cazas de las brujas, los procedimientos y experimentos a los que eran sometidos las mujeres al ser diagnosticadas como histéricas, la privación del placer femenino, las venus anatómicas, la lucha sobre nuestro derecho al aborto, son solo algunos ejemplos de la crueldad del conocimiento científico sobre la anatomía femenina como una política de dominación. Como si alguien siempre supiera más que nosotras y eso les da el derecho a decidir.

Apropiarme de los rastros visuales de los mecanismos usados para cerrar heridas de la medicina occidental, como las puntadas quirúrgicas, permite aproximarme al cuerpo desde una etapa de cicatrización en la que éste busca sanar un trauma. A mis obras más escultóricas las llamo pinturas hinchadas, aludiendo a un proceso interno de reconstrucción. Pienso las costuras médicas como momentos de censura al cuerpo para que no ocurra un desborde. Los cuerpos que hago hablan desde la llaga, una llaga que se establece como un portal a una cosmología privada. Es una práctica que desdobla las jerarquías entre trenzas y tripas, costillas y pestañas… donde los ombligos y las pupilas son intercambiables.

La disección de los cuerpos que propongo responde a un entendimiento del interior de mi cuerpo desde la metáfora y desde la posibilidad de autoficcionar lo que sucede dentro, partiendo del enigma de no poder visualizar lo que mi piel envuelve y de la frustración de saber que la información con la que me aproximo a mis interiores está contaminada y atravesada por un ente patriarcal. Creo que hay una potencia, e incluso una radicalidad, en permitir imaginar la anatomía femenina desde la fantasía. Un fémur puede tener un rostro, un intestino puede ser la cola que acompaña a una mujer de perfil —convirtiéndola en una sirena— y una pelvis puede ser una mariposa que mueve sus alas intermitentemente antes de que el suelo la reclame.

RCC: Se ha mencionado que algunas de tus piezas están vinculadas con el cine. Me llama la atención especialmente The Brood de David Cronenberg, un autor que en su primera etapa se inclinaba por la exposición de los cuerpos y la sangre. ¿Cuál fue tu acercamiento al cine de Cronenberg?

El cine es uno de los recursos visuales y narrativos en los que más me he apoyado recientemente. Tal vez esa afinidad esté vinculada a la relación que veo entre el cine y una buena pintura, la cual acuerpa miles de encuadres en una sola imagen fija, provocando que el ojo esté en constante movimiento. Cronenberg es uno de los muchos directores que he estado revisando que lidian con el cuerpo y la abyección. Lo que me emociona particularmente de Cronenberg es que hace de los interiores del cuerpo un artefacto que, al verlo, invoca una especie de wormhole o túnel que facilita un intercambio fluido entre el adentro y el afuera del cuerpo, como si estos dos planos tuvieran lugares y temporalidades distintas. The Brood (1979) fue particularmente importante porque trata de un cuerpo femenino que engendra unos cuerpos a partir de los humores de la protagonista. Las armas de Existenz (1999) han influenciado mi paleta de color (también un guiño a Eva Hesse, otra maestra del látex); en Crash (1996), me interesa cómo una de las personajes erotiza la herida abierta que tiene en la pantorrilla.

Roman Polanski también ha sido muy significativo para mí, especialmente en Rosemary’s Baby (1968) con Mia Farrow y en Repulsion (1965) con Catherine Deneuve. En ambas hace presente los dolores internos, tanto psíquicos como fisiológicos, a través de los cambios en la apariencia de sus protagonistas, como síntomas o momentos de alarma que señalan el terror que está ocurriendo dentro del cuerpo de estas mujeres, al cual no tenemos acceso con nuestros ojos. Por otro lado, The Bitter Tears of Petra Von Kant (Fassbinder, 1972) y Cries and Whispers (Bergman, 1973) me interesan porque la materialidad que alude al interior del cuerpo no está en el cuerpo o en un prop, pero está en el espacio y la escenografía que contiene a las figuras. En ambas películas, las protagonistas están eternamente enmarcadas por habitaciones rojas, como si estuvieran dentro de un cuerpo más grande del que nunca logran salir; casi como órganos o fetos.

Estoy consciente de que todas las referencias que acabo de nombrar vienen de directores masculinos, varios con historias personales agresivas. Sin embargo, no creo productivo negar que mi repertorio visual tanto del cine, como de la pintura, viene de miradas del cuerpo masculinas porque es sintomático del sexismo dentro de ambas disciplinas, y del sexismo en las interpretaciones del cuerpo de la mujer históricamente. El imaginario masculino impregnado e internalizado por el cuerpo femenino es un material que utilizo para poder engendrar cuerpos que citan los signos de estas concepciones mientras que los ponen en tensión. Esto no excluye la responsabilidad continua de consumir e integrar voces de directoras como Julia Ducournau, Agnès Varda, Céline Sciamma, Rebecca Miller, Věra Chytilová, Agnieszka Smoczynska y Suzan Pitt, cuyas obras proponen una reflexión profunda sobre la forma en la que figura un cuerpo femenino y los muchos espectros que éste puede habitar y deshabitar.

RCC: En ese mismo sentido, está la relación con la moda de Alexander McQueen. Aquí quisiera que nos explicaras si la relación de tus piezas está vinculada a los diseños de McQueen o también a sus presentaciones/performance, que en su momento fueron experimentales y polémicos y le ganaron el sobrenombre de el enfant terrible de la moda.

NC: Alexander Mcqueen ha sido uno de los artistas que más me han inspirado desde mi primer acercamiento a él, más o menos cuando tenía 14 años y vi el video Bad Romance de Lady Gaga (2009). McQueen decía que todos sus diseños los hacía sobre el cuerpo, pensándose como un cirujano plástico. Con sus prendas, lograba una arquitectura corporal que trascendió las anatomías humanas de quienes las usaban (aquí es importante nombrar a Thierry Mugler y Jean Paul Gaultier que también han sido referencias importantes en relación a prendas que funcionaban como armaduras de deformación para la anatomía femenina). Sin embargo, lo que me seduce de las piezas de McQueen es que en cada look lograba mostrar elementos que corresponden al interior y al exterior del cuerpo simultáneamente, combinando una pluralidad de materiales exquisita y poética, con una técnica que hacía a sus cortes tener una franqueza casi sádica. McQueen decía que quería que la gente le tuviera miedo a las mujeres que vestían su marca, y me relaciono con ese deseo. Busco que mis obras y que los cuerpos femeninos que retrato sean intimidantes a primera vista, pero que tengan una riqueza material que interrumpa la inmediatez de su consumo, apostando por una intimidad visual que complejiza la aproximación del espectador con la obra. Aunque los imaginarios que manejo son crudos, el cuidado y el tiempo evidenciado por la propia materialidad de la obra, pone en tensión el contenido visceral de la imagen que de alguna manera se reafirman y contradicen como un holograma.

Cuando estaba pensando en el show de Venus Atómica en Galería Karen Huber, tenía muy claro que las pinturas hinchadas que irían en la exposición no podían ser presentadas dentro de un cubo blanco. Sentía que, si ya logré emancipar a las figuras femeninas de la estructura híper masculina del bastidor, y habiendo logrado un desdoble en la forma de representar mujeres dentro del campo pictórico, presentarlas en un cubo blanco sería volverlas a encerrar. Desde Venus Atómica me quedó muy claro que crear un ambiente para los objetos es vital para mi obra; siento que el cubo blanco funciona como un aeropuerto del arte, un espacio que anula los contextos. Definitivamente esto está nutrido por las ambiciosas pasarelas de McQueen, que aclimataron cada una de sus colecciones y rompían con la expectativa comercial de su disciplina, apostando por mostrar la totalidad de su rico universo.

Desde la pubertad leo NYLON y Vogue de manera voraz; en ese momento yo tenía el sueño de ser diseñadora de moda y creo que eso ha influenciado mi forma de ver y hacer objetos. Creo que el arte es el objeto de lujo por excelencia y me es importante estar en diálogo no solo con los objetos de lujo de alta moda, sino también con su publicidad, aparadores y tiendas que crean el ambiente ideal para que cualquier cosa se vuelva un objeto de deseo. La crueldad con la cual esta industria nos ha enseñado a desear cosas como símbolo de estatus no es tan diferente a lo que ocurre en el mercado del arte como símbolo de capital cultural y social. Para mí, la alta moda y el arte ocupan una ambivalencia freudiana en la cual ocupan amor y odio simultáneo, ya que representan una belleza y ostentosidad muy seductora a expensas de ecosistemas opresivos y violentos. Es un ejercicio constante y paradójico de ser crítica ante mis propios fetiches (el arte incluido).

RCC: ¿En qué mujeres de la vida real te inspiras para tus creaciones: en ti misma, en tus familiares, en amigas, en personajes históricos…?

NC: El personaje histórico que más me ha inspirado y he tenido la necesidad de estudiar últimamente es María Magdalena. Siempre me han conmovido muchísimo las imágenes de vírgenes porque siento que son cuerpos femeninos secuestrados para ilustrar una ideología. Mi curiosidad por María Magdalena nació desde que vi una representación suya en la cual todo su cuerpo, a excepción de la cara, pechos, manos y pies, está cubierto de pelo, como si fuera un animal. No entendía de qué manera se tuvo que haber deformado la historia de esta mujer para que se justifique esa iconografía. La mutación del cuerpo de María Magdalena, forrada de pelo, corresponde a la mutación de la historia del mismo personaje, siempre adaptándola al estereotipo de la mujer perversa du jour. Aunque estas iconografías de denigración alimentan roles de género que siguen vigentes, me siento muy atraída por la poesía de las decisiones de cada una de estas representaciones. Quiero pensar que esa mutación casi interespecie de mujer animal nos puede llevar a esperanzas anatómicas poderosas, donde la animalidad no sea un signo de vergüenza, sino de ferocidad.

Por otro lado, me gusta pensar que Eva Hesse y Francesca Woodman son mis mejores amigas platónicas, quienes me acompañan y nutren de fe mis procesos. Creo que ambas (Hesse en sus autorretratos fantasmagóricos tempranos y sus pinturas de látex) lograron hacer del cuerpo un espectro anunciado desde la ultra corporalidad, alzando al cuerpo femenino a otro eje, o trayendo estos cuerpos desde portales oscuros para que habiten de manera efímera en nuestro terreno. Creo que la afinidad, cariño e inspiración que se le puede tener a otra persona trasciende la contemporaneidad, o más bien, que la contemporaneidad es más sobre el habitar de ideas y emociones, que de compartir un tiempo.

Swollen paintings: The Female Body From the Metaphor and the Self-fiction

Nicole Chaput’s work comes from a process of introspection that, at the same time, becomes a critique on cultural imaginaries around the female body. In her swollen paintings, as she calls them, a series of symbolic references converge that have been imposed on the female anatomy from the images of art, cinema, science, fashion, pop, etc., to be later transformed into ficional pictorial-sculptural objects. In this conversation, Chaput delves into the foundations of her work.

Regina de Con Cossío: Your pieces often seem like references to the world of medicine: the organs are exposed; the dissection of the bodies simulates an analytical study. How do you relate your artistic process with medicine, in particular with anatomy?

Nicole Chaput: Coral aggression occurs when these creatures spit out their guts to attack their neighbors and defend their territory. The mouth vomits up visceral mass, pushing digestive enzymes to dissolve its adversaries. After suffocating adjacent creatures, the coral swallows their guts. Like the coral, the internal spill becomes a strategy of resistance and survival in my artistic practice where I claim the territory and agency of my body and its boundaries in regular danger of being breached and extinguished.

The interior of female bodies in Western medicine has been interpreted and analyzed to be oppressed and marginalized, both the interior (reproductive capacities) and exterior (objectification, sexualization, desire education) of the female body have been articulated according to patriarchal views and agendas. From the witch hunts, the procedures and experiments to which women were subjected when diagnosed as hysterical, the deprivation of female pleasure, the anatomical Venus, and the fight over our right to abortion, are just a few examples of the cruelty of the scientific knowledge about female anatomy as politics of domination. As if someone always knew more than us and that gives them the right to decide.

Appropriating the visual traces of the mechanisms used to close wounds in Western medicine, such as surgical stitches, allows me to approach the body from a healing stage, where it seeks to heal a trauma. I call my most sculptural works puffy paintings, alluding to an internal process of reconstruction. I think of medical seams as moments of censorship of the body so that an overflow does not occur. The bodies I make speak from the wound, which is established as a portal to a private cosmology. It is a practice that unfolds the hierarchies between braids and guts, ribs and eyelashes…where navels and pupils are interchangeable.

The dissection of the bodies that I propose responds to an understanding of the interior of my body from the metaphor and from the possibility of self-fictioning what happens inside; starting from the enigma of not being able to visualize what my skin envelopes, and from the frustration of knowing that the information with which I approach my interiors is contaminated and influenced by a patriarchal entity. I think there is a power, and even a radical nature, in allowing the female anatomy to be imagined from fantasy. A femur can have a face, an intestine can be the tail that accompanies a woman in profile, turning her into a mermaid, and a pelvis can be a butterfly that flaps its wings intermittently before the ground claims it.

RCC: It has been mentioned that some of your pieces are linked to cinema. I am especially struck by The Brood, by David Cronenberg, a film director who in his early stage was inclined to expose bodies and blood. What was your approach to Cronenberg’s cinema?

NC: Cinema is one of the visual and narrative resources that I have relied on most recently. Perhaps that affinity is linked to the relationship I see between cinema and a good painting, which encompasses thousands of frames in a single image; causing the eye to be in constant motion. Cronenberg is one of the many directors I’ve been reviewing who deal with the body and abjection. What particularly excites me about Cronenberg is that he makes the interiors of the body into an artifact that, when seen, invokes a kind of wormhole or tunnel that facilitates a fluid exchange between the inside and the outside of the body, as if these two planes had different places and time frames. The Brood (1979) was particularly important because it deals with a female body that generates bodies from the moods of the protagonist. Arms from Existenz (1999) have influenced my color palette (also a nod to Eva Hesse; another latex master); in Crash (1996) I am interested in how one of the characters eroticizes the open wound she has on her calf.

Roman Polanski has also been very significant to me, especially in Rosemary’s Baby (1968) with Mia Farrow and in Repulsion (1965) with Catherine Deneuve. In both, he makes present the internal pains, both psychic and physiological, through the changes in the appearance of the protagonists, as symptoms or moments of alarm that signal the terror that is occurring within the body of these women, to which we do not have access with our eyes. On the other hand, The Bitter Tears of Petra Von Kant (Fassbinder, 1972) and Cries and Whispers (Bergman, 1973) interest me because the materiality that alludes to the interior of the body is not in the body or in a prop, but is in the space and the scenery that contains the figures. In both films, the protagonists are eternally framed by red rooms, as if they were inside a larger body that they never manage to get out of; almost like organs or fetuses.

I am aware that all the references I have just named come from male directors, several with aggression records. However, I do not think it is productive to deny that my visual repertoire, both in cinema and painting, comes from male views of the body because it is symptomatic of sexism within both disciplines, and of the historical sexism in the interpretations of the female body; the masculine imaginary impregnated and internalized by the feminine body is a material that I use to be able to engender bodies that cite the signs of these conceptions while putting them in tension. This does not exclude the continuous responsibility of consuming and integrating the voices of directors such as Julia Ducournau, Agnès Varda, Céline Sciamma, Rebecca Miller, Věra Chytilová, Agnieszka Smoczynska and Suzan Pitt, whose works propose a profound reflection on the way in which a body figures feminine and the many specters that it can inhabit and uninhabit.

RCC: In that same sense, there is the relationship with the fashion of Alexander McQueen. Here I would like you to explain to us the relationship of your pieces to McQueen’s designs and to his presentations / performances, which at the time were experimental and controversial and earned him the nickname of the enfant terrible of fashion.

NC: Alexander McQueen has been one of the artists that has inspired me the most since my first approach to him, more or less when I was 14 years old and saw Lady Gaga’s Bad Romance video (2009). McQueen said that all his designs were made on the body, thinking of himself as a plastic surgeon. With his garments, McQueen achieved a body architecture that transcended the human anatomies of those who wore them (here it is important to name Thierry Mugler and Jean Paul Gaultier who have also been important references in relation to garments that functioned as deformation armor for the female anatomy). However, what seduces me about McQueen’s pieces is that in each look he managed to show elements that correspond to the interior and exterior of the body simultaneously, combining a plurality of exquisite and poetic materials, with a technique that made his tailoring have an almost sadistic frankness. McQueen said that he wanted people to be afraid of the women who wore his brand; and I relate to that desire. I seek that my works and that the female bodies that I portray are intimidating at first sight, but that they have a material richness that interrupts the immediacy of their consumption, betting on a visual intimacy that complicates the viewer’s approach to the work. Although the imaginaries I handle are raw, the care and time evidenced by the same materiality of the work puts the visceral content of the image in tension, which somehow reaffirms and contradicts itself, like a hologram.

When I was thinking about the Venus Atómica show at the Karen Huber Gallery, it was very clear to me that the bloated paintings that would go in the exhibition could not be presented inside a white cube. I felt that, if I had already managed to emancipate the female figures from the hyper-masculine structure of the frame, and having unfolded the way of representing women within the pictorial field, to present them in a white cube would be to enclose them again. From Venus Atómica it became very clear to me that creating an environment for objects is vital for my work; I feel that the white cube functions as an art airport, a space that annuls contexts. Definitely this is nurtured by McQueen’s ambitious catwalks, which acclimatized each of his collections and broke with the commercial expectation of his discipline, betting on showing the entirety of his rich universe.

Since puberty I read NYLON and Vogue voraciously; at that time, I had the dream of being a fashion designer and I think that has influenced my way of seeing and making objects. I believe that art is the luxury object par excellence, and it is important for me to be in dialogue not only with high fashion luxury objects, but also with their advertising, window displays and shops that create the ideal environment for anything to become an object of desire. The cruelty with which this industry has taught us to desire things as a status symbol is not so different from what happens in the art market as a symbol of cultural and social capital. For me, high fashion and art occupy a Freudian ambivalence; in which they occupy simultaneous love and hate since they represent a very seductive beauty and ostentatiousness at the expense of oppressive and violent ecosystems. It is a constant and paradoxical exercise of being critical of my own fetishes (art included).

RCC: In what women from real life do you get inspiration from in order to make your creations? yourself, your relatives, friends, historical figures…?

NC: The historical character that has inspired me the most and that I have had the need to study lately is María Magdalena. I have always been very moved by the images of virgins because I feel that they are female bodies kidnapped to illustrate an ideology. My curiosity about Mary Magdalene was born when I saw a representation of her in which her entire body, except for her face, breasts, hands and feet, was covered with hair, as if she were an animal. I did not understand how the history of this woman had to have been distorted to justify that iconography. The mutation of the body of María Magdalena, lined with hair, corresponds to the mutation of the story of the same character, always adapting her to the stereotype of the perverse woman du jour. Although these iconographies of denigration feed gender roles that are still in force, I feel very attracted by the poetry of the decisions of each of these representations. I want to think that this almost interspecies mutation of the animal woman can lead us to powerful anatomical hopes, where animality is not a sign of shame, but of ferocity.

On the other hand, I like to think that Eva Hesse and Francesca Woodman are my best platonic friends, who accompany me and nourish my processes with faith. I believe that both (Hesse in her early phantasmagorical self-portraits and her latex paintings) managed to make the body a specter announced from the ultra-corporality, raising the female body to another axis, or bringing these bodies from dark portals so that they ephemerally inhabit our land. I believe that the affinity, affection and inspiration that you can have for another person transcends contemporaneity, or rather, that contemporaneity is more about inhabiting ideas and emotions than sharing time.