Art & Architecture

Buildings are more than just places where people go to work or to live. They are a way for people to express creativity, to push the limits of what makes something useful and a work of art.

These four buildings exemplify the union of art and architecture, where beauty and wonder combine in an object created for everyday use. These artists were (and are) leaders and visionaries in their field, and these works illustrate the effect that the combination of art and construction can have on society.

Donald Judd House

The impressive 19th century, 5-story, cast-iron building found at 101 Spring Street is artist Donald Judd’s New York legacy. While much of his success was built in Marfa, Texas, his beginning occurred here in New York. The renovation of his house-turned-museum was started in 2011 and completed in 2013, including repairs to the cast-iron façade, numerous new windows & frames, and updates to the interior of the home to meet modern safety regulations. This historical (pre-electricity) building was, unlike many other large buildings of its era, not torn into offices and smaller spaces, but used as a home and studio for Judd, who raised his family, created many works of art, and welcomed other artists.

Judd, considered by many as a father of minimalism and a leader of modern art, made it a point to stay far away from the art “establishment,” and spent early years as an art critic, and most of his adult life writing. As a philosopher by education (graduating from Columbia University with a B.S. of Philosophy in 1953), it is not far-fetched to see his displeasure with traditional works of art in his own architectural style. His belief in utilizing what already exists is exemplified here, as in 1968 he purchased the 1870 cast-iron structure and immediately opened the floorplan up and lived in all 5 stories of the expansive building. The plans and work were modified throughout the process, as his ideas morphed during each phase.

Judd’s grown children are at the heart of the preservation, as they understood the importance of his life and work in NYC (or simply wanted to recall their childhood memories). Perhaps by preserving and highlighting their father’s work, his belief in simplicity of space can be appreciated by future generations.

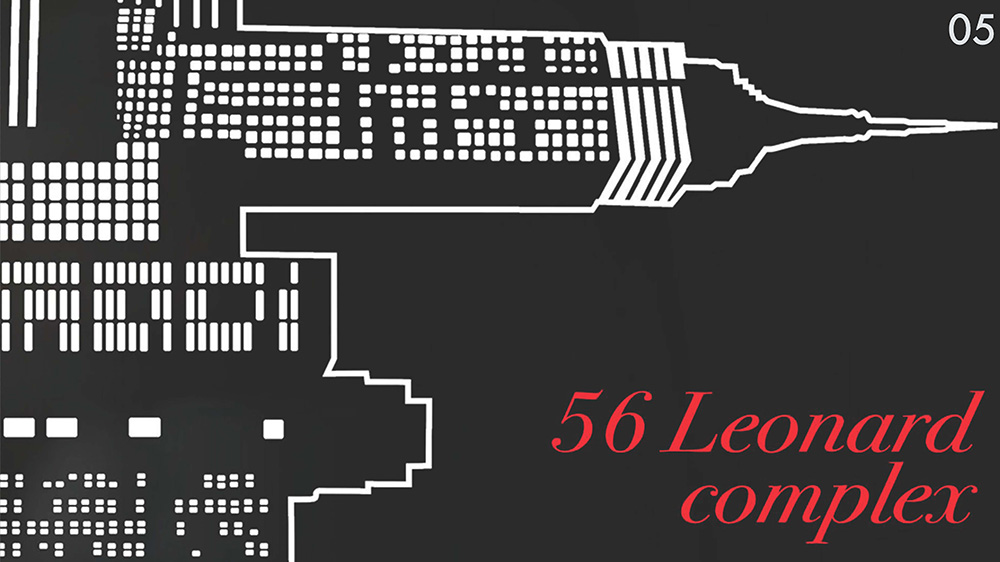

Leonard Complex

The 60-story structure is the largest residential tower in Manhattan’s Tribeca neighborhood, and just one example of the growth of “super slender” towers in NYC exhibiting extreme heights combined with narrow bases. Construction began in 2008, but a lack of funding stalemated the project shortly afterward. It commenced again in 2012 and was completed in 2015.

Designed by the Swiss architectural firm of Herzog & de Meuron, this breathtaking piece of art was conceptualized with a theory of “pixelation,” where individual living spaces were gathered together on each level. With the distinctions of each unit, the building was filled with unique apartment floorplans, including what appeared to be random balconies and terraces. The structure appears even more unplanned towards the top, as the ten distinct upper penthouses grace each level, complete with expansive windows.

This architectural duo are no strangers to accolades; receiving the 2001 Pritzker Prize, the highest honor awarded in architecture, they are known for their creation of Tate Modern in London, the Forum Building in Barcelona, the Allianz Arena in Munich, and the Walker Art Center expansion in Minneapolis. Their commitment to minimalism, use of innovative products, and focus on geometric shapes makes their work iconic and enduring.

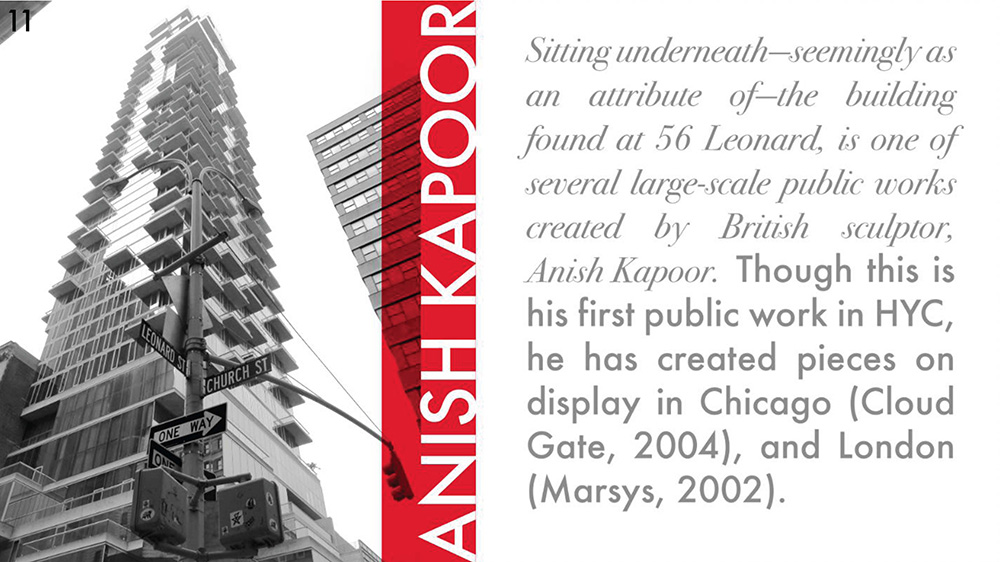

Anish Kapoor’s Sculpture

Sitting underneath—seemingly as an attribute of—the building found at 56 Leonard, is one of several large-scale public works created by British sculptor, Anish Kapoor. Though this is his first public work in HYC, he has created pieces on display in Chicago (Cloud Gate, 2004), and London (Marsys, 2002).

Oculus

Designed to focus light into the train station and shopping center, Oculus appears as a set of wings to some viewers, and a dinosaur ribcage to others. The curved steel walls rise 160 feet in an immense white skeleton, light dancing through the thick beans. The heart of the space is shone upon by a skylight extending the length of the impressive structure.

Spanish sculptor Santiago Calatrava is no stranger to over sized architecture, as his rail station in Lyon, France and a museum in Milwaukee attest. Rail stations are his specialty, but this modern structure brings more to the World Trade Center than simply a transportation hub. This provides another example of beauty, built adjacent to the nearby World Trade Center memorial, and perhaps a whisper of museum atmosphere. He was inspired by the heart of New Yorkers’ their determination to carry on after such a tragedy as 9-11. After so much of their world was destroyed, Oculus provides a breath of air, and of daylight, as shown in the expansive white walls and ceiling, and the retractable roof. No matter the everyday, confined feeling New Yorkers may experience in the trains down below, in small apartments and buildings found within the crowded location of NYC, visitors enter a vast space in Oculus, open for people to move about, and brightly lit, as to welcome a new dawn.