How does Pictorial Art Represent Pandemics?

By Julio Horta

Referring to the philosopher Luigi Pareyson, Umberto Eco proposes in The definition of Art that “the person forms in the work his concrete experience, his inner life, his inimitable spirituality, his personal reactions in the historical environment in which he lives…” In relation to this “aesthetics of formativity”*, images about a pandemic in art are forms that establish the way the artist looks at himself in his social reality.

Some of the earliest representations we found in Medieval Art illustrations: they portray the Black Death that affected Eurasia in the 14th century. Some scenes and religious narratives about this epidemic inspired artists such as Pieter Brueghel “the Elder” (Breda, 1525 – Brussels, 1569), who captured in an oil painting the apocalyptic scene The Triumph of Death (1562), an example of anguish medieval post-plague. The look on the disease has been a recurring theme in art. We review 5 of the most important works in history to explore the artists’ vision and their aesthetic problematization of pandemics.

Francisco de Goya shows a particular perspective: to look at the patient in his confinement. In this work, looking at the epidemic implies looking at the disease itself at a distance: in 1792 Goya (Fuendetodos, 1746 – Bordeaux, 1828) had contracted a disease that caused him permanently deaf. The convalescence caused a radical change in the content of his images. The representation of death was a constant topic in his world view. His image shows sick people piled up and imprisoned in the back of a hospital due to an epidemic.

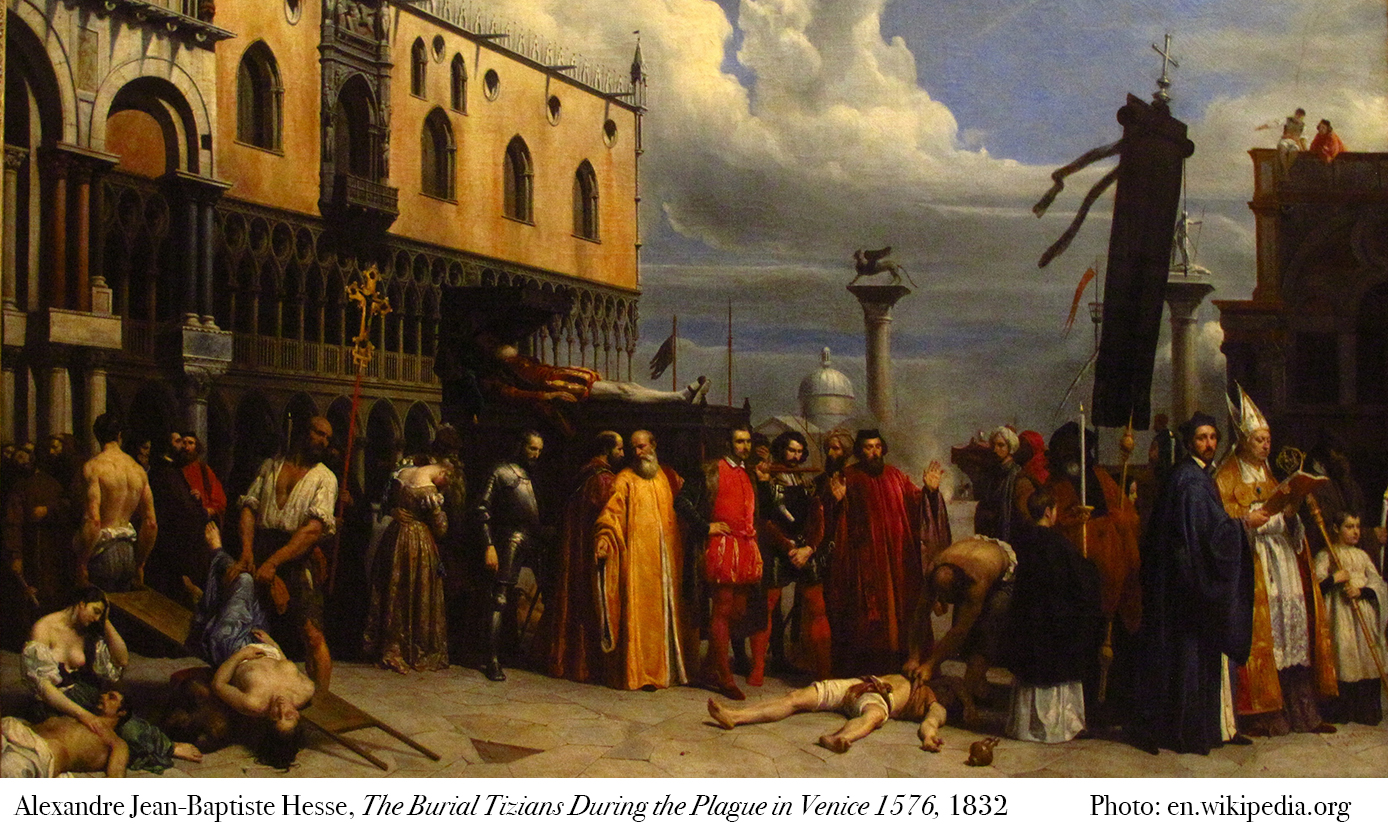

Safeguarded in the Louvre Museum (Paris), this painting by Alexandre Jean-Baptiste Hesse (Paris, 1806-1879) is a reminder of the effects of an epidemic. Dedicated to the death of the Venetian painter Vecellio di Gregorio “Tiziano” (Pieve di Cadore, 1477 – Venice, 1576), the painting shows the anodyne look of nobles and clergymen facing an epidemic that began in Venice, and spread to Italy due to the effect of the rat flea bite. It’s interesting the position of the clerics who are located in front of a procession: this detail recalls the public invocation of the church and the Senate of the city (September 1576) to agree on the construction of a religious temple in case that the epidemic decreased its mortality.

The look of an epidemic does not always have the drama of a realistic scene. Arnold Böcklin (Basel, 1827 – Fiesole, 1901), the subject requires an allegorical treatment: making a visual metaphor of the horsemen of the apocalypse, the epidemic has the form of death riding on a winged serpent; a spectral scene where the plague, dressed in black and brandishing a scythe, walks the streets leaving dead and disease in its wake. This scene corresponds to a topic that is obsessively repeated in Arnold Böcklin’s paintings: death, war, hunger and disease.

With a life marked by disease (he lost his mother and sister to tuberculosis), for Edvuard Munch (Løten, 1863 – Skøyen, 1944) the epidemic has the image of his own face. After suffering and surviving the “Spanish flu” between 1918 and 1919, the painter decided to show himself in a self-portrait that blurs the features of his sick face, framed by a languishing body covered by blankets that evoke physical fragility after illness. The work currently remains at the Oslo National Gallery.

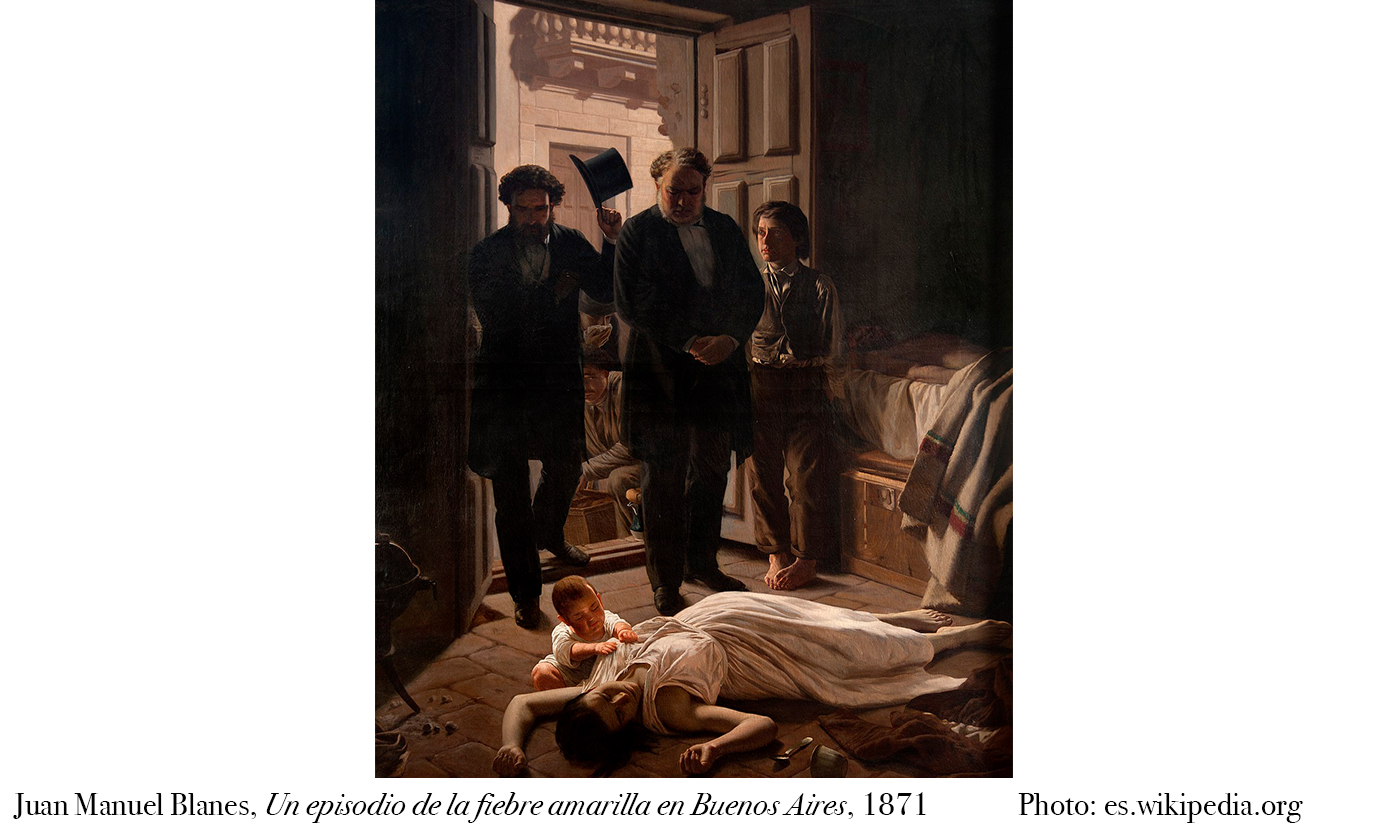

Known as “the painter of the homeland”, Juan Manuel Blanes (Montevideo, 1830 – Pisa, 1895) represents in this image a dark and melancholic scene that evokes the moment when two Freemason representatives of the Popular Commission enter a room to notice the death of a couple because of the epidemic. This Commission was formed as a response from citizens to the lack of government assistance. The episode visualized by the artist closes with the image of a boy holding the chest of his deceased mother. In the background lies the father’s body. This true fact was reported by the newspapers of the time, and it’s the most representative event of the epidemic in Buenos Aires due to its burden of misery and pain.

*Author’s translation. The translation belongs to the Spanish edition La definición del arte, Martínez Rocca editorial.

**No English translation

Julio Horta is a PhD student in philosophy. Professor of language sciences at UNAM, the Iberoamerican University and the Autonomous University of the State of Morelos, he has collaborated in colloquia, lectures and research in semiotics for more than 10 years. He has collaborated on various semiotic books. His most recent publication is Sociosemiótica y cultura. Semiotics principles and analysis models.