Art Decade

John Baldessari, the eternal return

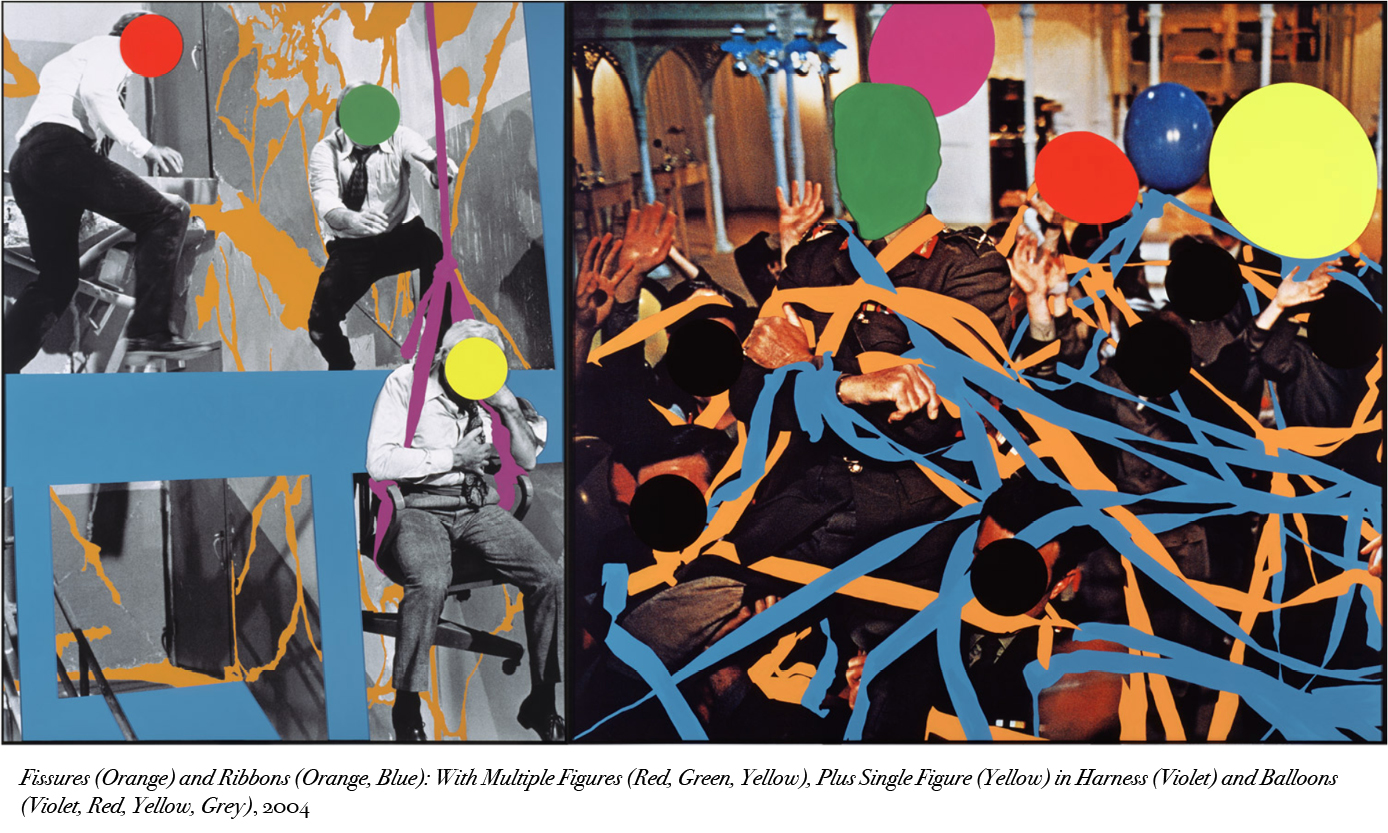

Last Thursday, January 2, one of the most important names of conceptual art died at age 88. Creator of a complex work where written and visual language merges, Baldessari boldly mixed motives of everyday life in diverse formats where humor was the main character.

By Abel Cervantes

It is possible to imagine it: a man 6’7″ with a long beard wander through the city looking for a funeral home to attend his request. The man, however, doesn’t look for a service for a relative. Not even for a friend. Try to find a funeral home that burns paintings, the paintings he has done for more than a decade to start his career as an artist. Cremation Project (1970) – a glass cabinet with three objects: a bronze plaque where could be read “John Antonio Baldessari May 1953-March 1966”, a urn in a shape of a book and a notarized declaration witnessing what had just been happen: all the artist’s paintings had been cremated on July 24 in San Diego – it is important not only because with it Baldessari closed a cycle and inaugurated a more important one that would define him as an artist, but because with that gesture he opened a new possibility for artistic forms, where everything could take place. Humor included.

From then on, John Baldessari explored all kinds of formats and disciplines: photographs, architecture, installations, collages, artists’ books, comics, video… As he tells Calvin Tomkins in that magnificent profile, “No More Boring Art”, published in The New Yorkeron October 18, 2010: when I cremated my works“I thought about Nietzsche and the eternal return […] and equating the artist with the ‘body’ of his work, and so forth. The problem was that several local mortuaries refused to cremate paintings. I found one finally, but the guy said we had to do it at night.”

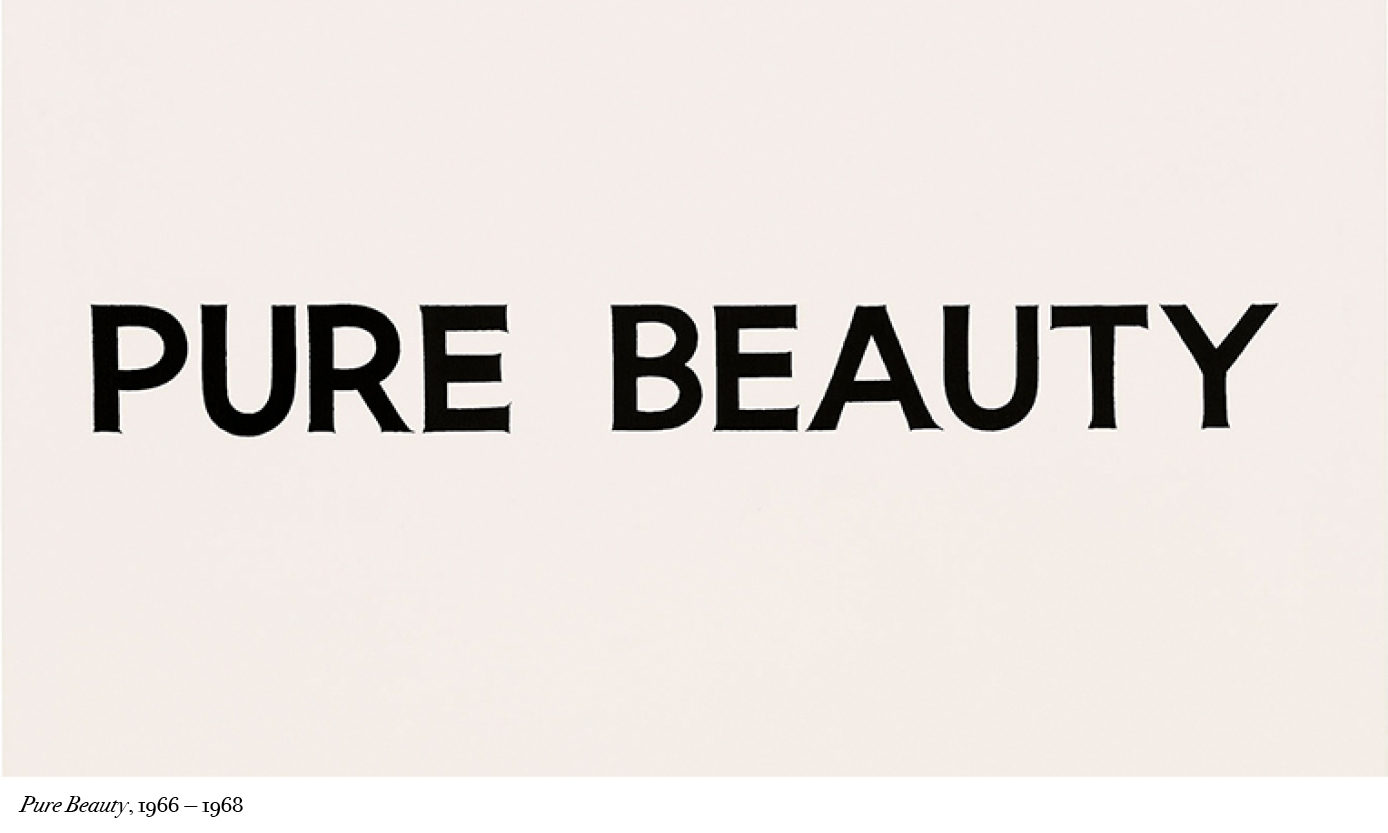

Thus John Baldessari had two births. The first took place on June 17, 1931 in California. The second, without exact date, goes around 1966 and 1968 when he worked inSemi-Close-Up of Girl by Geranium (Soft View), one of his most emblematic pieces by merging a series of interests that would pursue him for the rest of his life. The work consisting of a gray canvas contains a dialogue copied from Intoleranceby D. W. Griffith’s where you can read “Finishes Watering It—Examines Plant to See If It Has Any Signs of Growth, Finds Slight Evidence—Smiles—One Part Is Sagging—She Runs Fingers Along It—Raises Hand Over Plant to Encourage It to Grow.” “It’s probably my all-time favorite piece, he said. I just think it’s perfect—very simple, and you can imagine it so easily. David Foster Wallace once said that the duty of the writer is to make the reader feel intelligent, and let them fill in the gaps. I feel that way, too.”

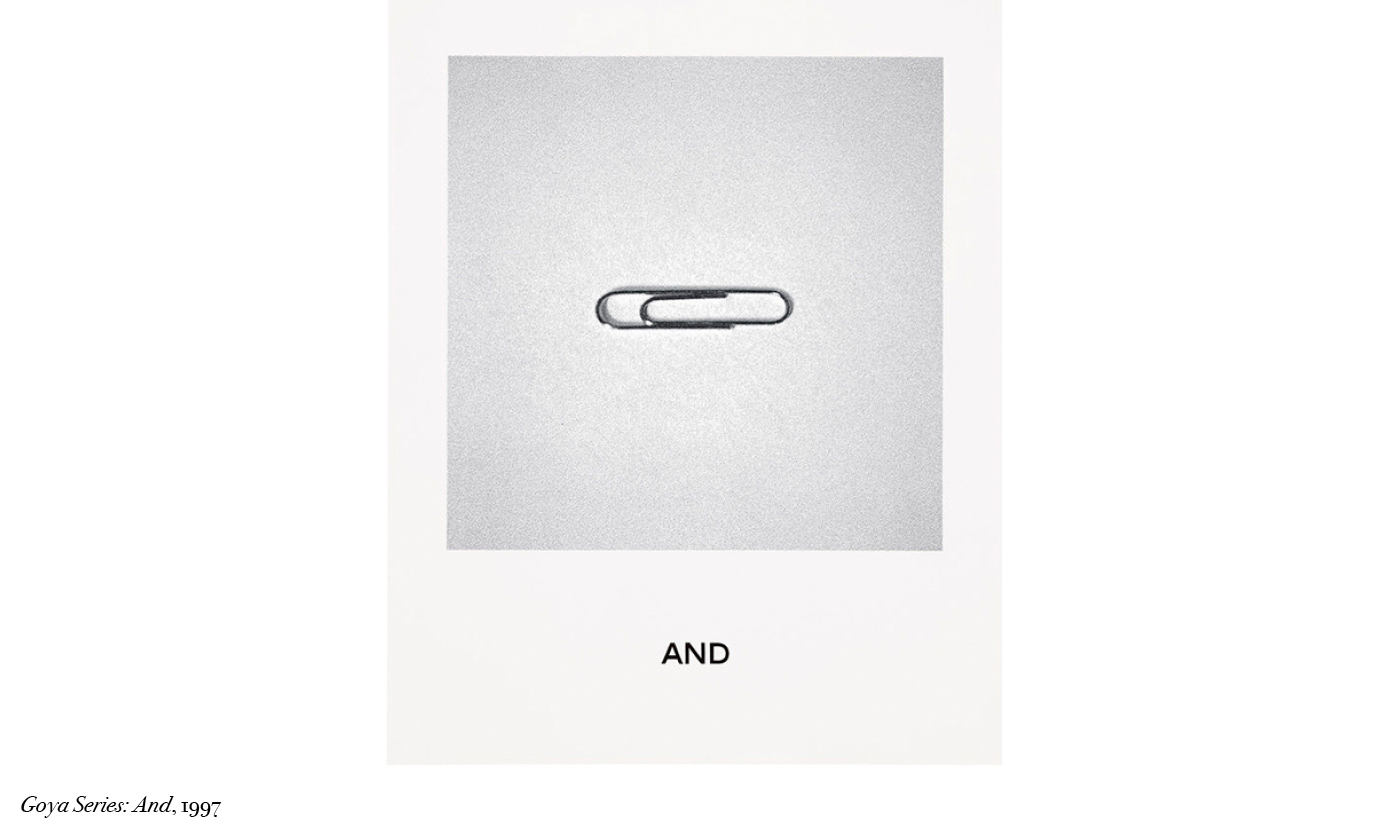

Baldessari was a kind of writer in art or an artist who played with language and writing. Related in that sense with his friend Lawrence Weiner, his powerful phrases dialogue with the images to open unexpected interpretations. Perhaps without knowing it, he began a path for the interpretation of contemporary art very close to the one that Roland Barthes promoted: unfolding the images in language to grab them. Find the beauty of the sounds of words to try to get closer to what seems unattainable.

But the artist had a concern beyond shapes, words or colors. Since he was young, he doubted his artistic activities because for Baldessari the most important thing was the social transformation of his environment. For more than 5 decades he alternated art with teaching, influencing artists with a thought similar to his own: if art is not a catalyst to change the horizon, let it be nothing. And what Tomkins tells:

Cal Arts was the result of a merger between the Chouinard Art Institute and the Los Angeles Conservatory of Music.Los Angeles Conservatory of Music. Conceived and lavishly funded by Walt Disney as an interdisciplinary school whose graduates would include a ready supply of talented Disney animators, it opened in 1970 (four years after Disney’s death), and quickly became the most radical art school in the country. Brach brought in Allan Kaprow, a prime instigator of the “happening” movement in New York, as assistant dean, and his faculty appointments included Nam June Paik, the progenitor of video art; the feminist artist Judy Chicago; and the Fluxus artists Dick Higgins and Alison Knowles. There were no formal classes, no grades, and no curriculum. Baldessari was supposed to teach painting, but he balked at that; he called his course “Post-Studio Art,” which meant anything other than traditional painting and sculpture. He hoped that by treating his students as “younger artists” he might be able, with luck, “to set up a situation where art might occur.”

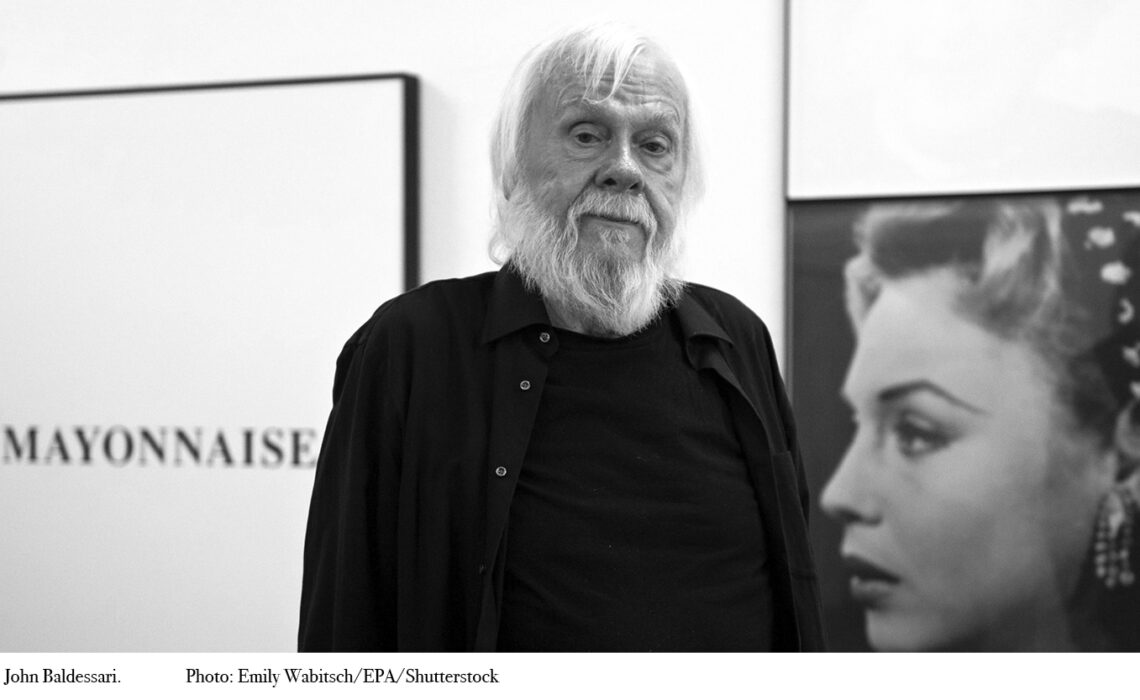

There is a portrait of Baldessari that I particularly like. His face is in profile and seems to turn towards the center, as if he wanted to look at us. I think about what are perhaps his most famous paintings: scenes from B-series movies or from everyday life in which the faces of the portrayed characters are covered by a circle. Sometimes green. Sometimes white, yellow or blue. What would happen if that portrait had one of those circles? Should it have half or two? How will we remember the old man with the white long beard? Like a madman, 6’7″,who burned his paintings to be reborn or as a curious man who borrowed images from anywhere to turn them into art? A father of conceptual art? A pop art genius? Perhaps as himself mentioned: “A hundred years from now, I will probably be remembered as the guy who put dots on faces.”