All that shines is Jeff Koons

By Mariel Vela

Jeff Koons is an undeniable figure, regardless of whether we agree with that statement or not. His work is practically inseparable from the shiny image he was forged of himself as an artist. Born January 21, 1955, in York, Pennsylvania, Koons studied painting at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and a BFA at the Art Institute of Maryland in Baltimore.

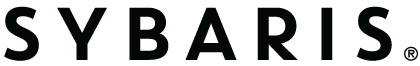

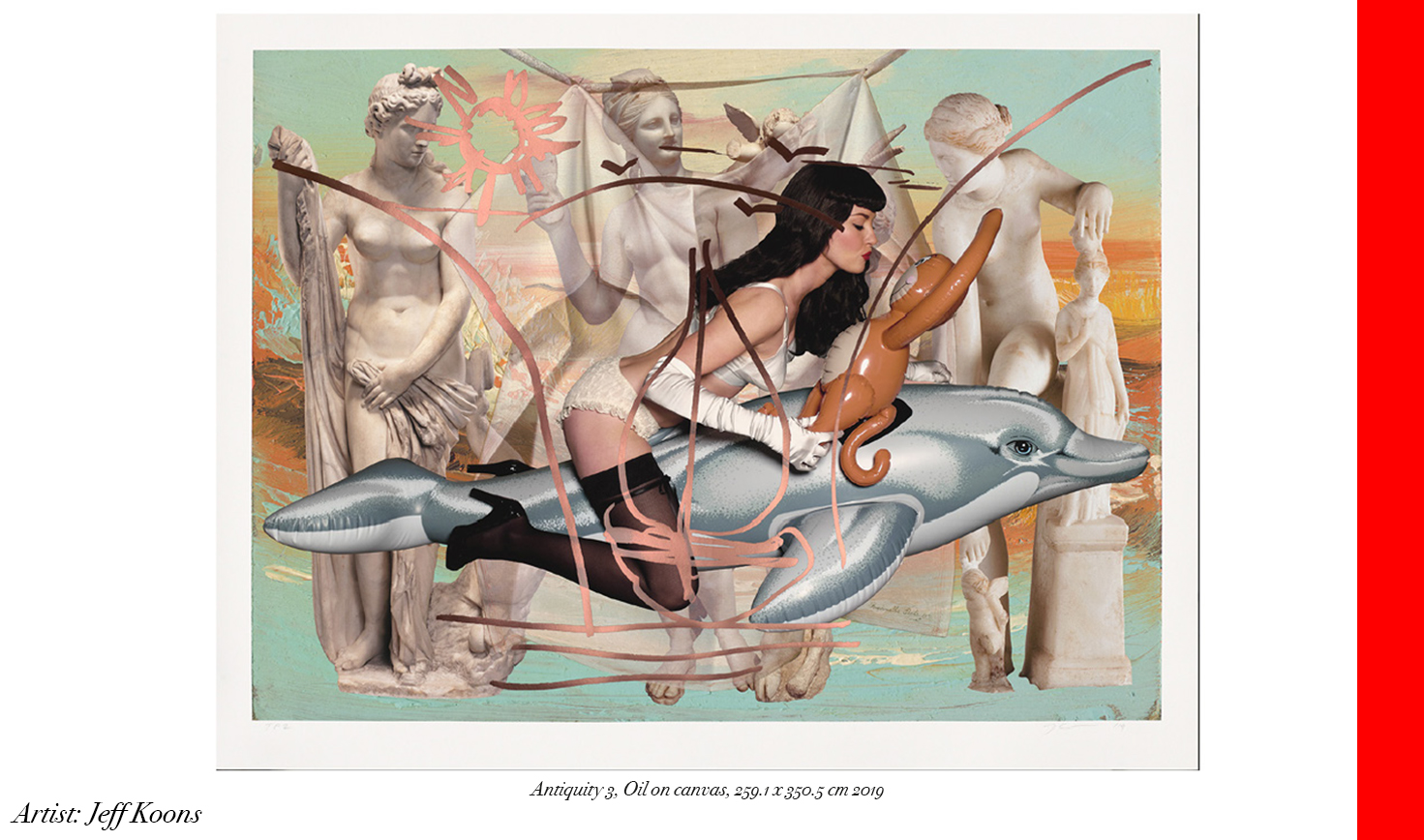

Painting has never been considered his main medium, although recent forays into an exploration regarding the role of the viewer’s gaze in classic art history paintings (in his Gazing Ball series) as well as the Antiquityseries have continued to expand on some of his most familiar subjects. What is the role of our gaze when it comes to his work? What messages do we help complete? Through industrially produced series of sculptures and objects Jeff Koons has ripped open our drives and desires, fulfilled through the beauty of consumer-culture, the glamour of merchandise and the aura that surrounds contemporary art in Western culture.

The artist has said repeatedly that his pieces have no occult hidden meanings, however this hasn’t appeased his most fervent admirers or critics. Preceded by figures like Salvador Dalí (whom Koons revered), Andy Warhol and Marcel Duchamps, Jeff Koons’ work inscribes itself in a narrative that belongs to a tradition that deconstructed the art apparatus through gestures and statements rather than through technical mastery. What is the difference between an art piece and merchandise? Who has the authority to decide what is art over what isn’t? The complicated symbolic relations manifest in art history, have been challenged repeatedly, changing the ways in which we as viewers relate to objects that can range from masterpieces to vacuum cleaners, or Brillo soap. One of the most valuable aspects of Koons’ approach has to do with discrediting art as an attainable experience for the selected few, his work is meant to be enjoyed and consumed visually by anyone chasing banality, visual pleasure, and sometimes explicit erotica. Along with Warhol and Dalí, the cult around celebrity meant that the artist went from being the producer of images to producing himself as an image. Some of these parallel themes have been explored in the recent exhibition Appearance Stripped Bare: Desire and the Object in the work of Marcel Duchamp and Jeff Koons, Even.(19.05.19 – 29.09.19) held at Museo Jumex, Mexico City.

In 1980, Koons’ work was displayed for the first time in the windows of the New Museum in New York. As if exhibiting products for sale, vacuum cleaners were installed in their most attractive angles with an ad that proclaimed: “The New”. This series, produced between 1979 and 1980, coincided with the period in which he worked as a stock broker for Wall Street. Even though Koons manifests that there is no big secret, “The New” could very well be a commentary on the complex relationship human beings sustain with their everyday objects, how the prospect of a new household appliance can incite excitement. To be part of a culture that has normalized waste, means that true value is symbolic, that our desire for “The New” is never quite satisfied. This worldview is characteristic of the rampant excesses of the 80s, especially in Manhattan, and perfectly captured in one of the artist’s most ostentatious works: Rabbit(1986), a piece that recently fetched $91 million dollars in 2019 at an auction in Christie’s.

As Roberta Smith wrote in a recent article titled “Stop Hating Jeff Koons”, it is fashionable and easy to discredit his work. However, how much of what we dislike is a reflection of that which we practice daily? As Koons has stated before: “There is bourgeois shame and guilt in responding to banality.” Banality was the name he gave to his 1988 series, inspired by Humboldt figurines, it depicted several famous characters in suggestive scenes, such as Michael Jackson posing with his pet chimpanzee Bubbles, dripped in gold paint, or Jayne Mansfield holding the Pink Panther. Many of these images have been controversial due to Koons’ copyright infringement accusations, again stirring debates on which images should be considered public property, who should receive royalties for them and also poses the question: what is the fine line that divides appropriation from illegality? Another series that provoked viewers was “Made in Heaven” from 1989 in which the artist and his then wife Ilona Staller (famously known as Cicciolina) appeared depicted in sexually explicit sculptures and images.

Jeff Koons is a controversial figure, one that has punctuated a peeping hole into the insulated art world. No one is safe from falling to the allure of his shiny surfaces and a social critique that slowly unravels once we think we have deciphered him. With Koons, what we see is what we don’t get. For someone known for his keen instincts on consumerism, he sure is the best at promoting the delayed gratification of making us wonder, all the time, whether everything is just what it appears to be. Is there a catch? Definitely.

Mariel Vela studied Art History at UNAM and continues to do independent research on experimental cinema and contemporary art.